Today in History, November 5: 1862 – President Abraham Lincoln relieves Gen. George B. McClellan of the command of the Army of the Potomac for the second and last time. “Little Mac” was a great organizer, and drilled the army into a very competent force…but refused to use it. On numerous occasions Lincoln suggested, cajoled, asked, and ordered McClellan to take offensive action. Gen. McClellan always assumed his enemy had many more soldiers than they actually had and found excuses not to advance. Finally Lincoln had enough. McClellan, who referred to Lincoln as a well meaning gorilla, would run against his boss for President as an anti-war Democrat. I read and listen to a lot of history. It always bothers me when an author judges a leader rather than just reporting the facts…we weren’t there, and I’ve been “second guessed” myself. Gen. McClellan is my exception. I’ve read too many historical accounts, too many biographies in which he was mentioned. I don’t believe he was a coward. I don’t necessarily believe he was a traitor. But he repeatedly and adamantly acted against the interest of his government. I would love to know what was in his mind.

Tag: lincoln

Hero John C. Freemont…Gets Himself Fired

Today in History, November 2: 1861 – President Lincoln relieves Gen. John C. Fremont of the command of the Western Department of the Union Army.

In his younger years Fremont had married Jessie Hart Benton, daughter of a successful US Senator. In the 1840’s he became an American hero exploring and mapping portions of the western US.

His popularity led him to become the first presidential candidate of the fledgling Republican Party, although he lost. While he and the second Republican candidate for president, Lincoln, may have shared political views, they didn’t share timing.

Fremont didn’t prove to be successful as a military commander in Missouri. As commander in the Western Department, he ordered all slaves in Missouri emancipated. Lincoln, who eventually would sign the Emancipation Proclamation, was not ready to do so in 1861 for fear that he would alienate the border states of Missouri, Kentucky, Delaware and Maryland, potentially losing their soldiers and resources to the Confederacy. Fremont refused an order to rescind his orders, and Lincoln fired him, a risky political move in itself due to Freemont’s popularity and connections.

Fremont was given a Mountain command in the east, but quit that when he became subordinate to Gen. Pope, who he felt he outranked. That ended his Civil War career, but he would eventually become Governor of Arizona territory. He passed away in New York in 1890.

Snatching defeat from the jaws of victory

Today in History, September 18: 1862 – Snatching defeat from the jaws of victory…again and for the last time. The Battle of Antietam in Maryland had drawn to a close the previous day. The bloodiest single day battle in American history, it can’t be said that either side “won” the battle, but it was a tactical victory for the Union. Lee had to retreat back to Virginia, Lincoln was able to announce the Emancipation Proclamation, and European powers decided not to recognize the Confederacy as a result. And yet, Union Major General George B. McClellan managed to let go of an advantage that could have ended the war much earlier, saving countless lives….

Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, arguably the most fierce force the South had at it’s disposal, 43,000 strong, was exhausted, demoralized, and had it’s back to the Potomac River. McClellan, who had 50,000+ in his Union army, a third of which (the portion under his immediate control) had not engaged in the battle, and with thousands of fresh reinforcements arriving by the hour, refused to engage with Lee, allowing the Army of Northern Virginia to escape across the Potomac. He then refused for over a month to give chase. McClellan had an incredible ego, but it was not commensurate with his abilities. He had a persistent knack for overestimating his enemies. He assumed that Lee had 100,000 troops, which was a ridiculous assumption…he had done this several times in his career…if he’d had a million troops, he would have said his enemy had five. President Lincoln and Chief of Staff Henry Halleck implored McClellan repeatedly to use the army he commanded, but he made excuse after excuse and refused. Finally, on November 9th, Lincoln fired him for the final time. McClellan would run against the President in ’64 on a platform calling for an end to the war without achieving victory (a platform he reportedly denounced.)

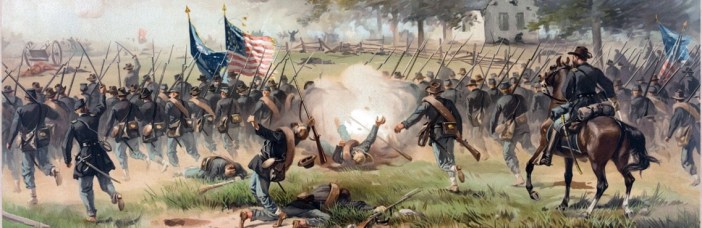

Bloody Antietam’s Importance

Today in History, September 17: 1862 – The Battle of Antietam during the Civil War. Confederate General Robert E. Lee made the first of several attempts at taking Washington, DC. The Army of the Potomac met Lee’s army at Antietam Creek to defend the city. Lee, Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson, and James Longstreet lead the Southern forces, While George McClellan, Ambrose Burnside and Joseph Hooker lead the Union forces. In 13 hours of fierce fighting, 23,000 of 100,000 combatants are killed or wounded, more in one day than all of America’s wars to that point, and the most American’s ever killed in a single day in our history. Typically, while Hooker’s and Burnside’s commands moved on their enemy, McClellan stayed in place, not engaging. The end of the battle found both armies where they were when it began. But Lee soon retreated back to Virginia. Two important consequences of the battle…it gave President Lincoln a victory that gave him the confidence to issue the Emancipation Proclamation, and European powers decided against recognizing the Confederacy.

“You’re a Lowlife SOB…Respectfully, Your Humble Servant….”

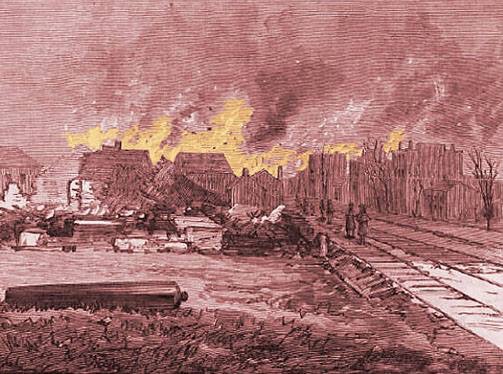

Today in History, September 7: 1864 – The evacuation of Atlanta.

Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s Army had taken Atlanta. Now, far from his supply base with threatened supply lines, he had to decide how to supply his army and the civilian population of the city he had conquered.

He decided to put the onus on the Confederate Army, and ordered all civilians to leave the city. They could go North or South, but go they must.

The Confederate mayor and the opposing General, Gen. John Bell Hood, were incensed. Now the Confederate Army, already suffering from lack of resources, also had to take care of the displaced populace. See below for the remarkable correspondence between Sherman, Hood and the Mayor. It fascinates me how, in the gentlemanly demeanor of the time, they called each other every name they could think of, and still ended their letters, “Respectfully, your humble servant….”

Maj. Gen. H. W. HALLECK, Chief of Staff, Washington, D.C.:

GENERAL: I have the honor herewith to submit copies of a correspondence between General Hood, of the Confederate army, the mayor of Atlanta, and myself touching the removal of the inhabitants of Atlanta. In explanation of the tone which marks some of these letters I will only call your attention to the fact that after I had announced my determination General Hood took upon himself to question my motive. I could not tamely submit to such impertinence, and I have seen that in violation of all official usage he has published in the Macon newspapers such parts of the correspondence as suited his purpose. This could have had no other object than to create a feeling on the part of the people, but if he expects to resort to such artifices I think I can meet him there too. It is sufficient for my Government to know that the removal of the inhabitants has been made with liberality and fairness; that it has been attended by no force, and that no women or children have suffered, unless for want of provisions by their natural protectors and friends. My real reasons for this step were, we want all the houses of Atlanta for military storage and occupation. We want to contract the lines of defenses so as to diminish the garrison to the limit necessary to defend its narrow and vital parts instead of embracing, as the lines now do, the vast suburbs. This contraction of the lines, with the necessary citadels and redoubts, will make it necessary to destroy the very houses used by families as residences. Atlanta is a fortified town, was stubbornly defended and fairly captured. As captors we have a right to it. The residence here of a poor population would compel us sooner or later to feed them or see them starve under our eyes. The residence here of the families of our enemies would be a temptation and a means to keep up a correspondence dangerous and hurtful to our cause, and a civil population calls for provost guards, and absorbs the attention of officers in listening to everlasting complaints and special grievances that are not military. These are my reasons, and if satisfactory to the Government of the United States it makes no difference whether it pleases General Hood and his people or not.

I am, with respect, your obedient servant,

W. T. SHERMAN,

Major-General, Commanding.

———————————–

General HOOD,

Commanding Confederate Army:

GENERAL: I have deemed it to the interest of the United States that the citizens now residing in Atlanta should remove, those who prefer it to go South and the rest North. For the latter I can provide food and transportation to points of their election in Tennessee, Kentucky, or farther north. For the former I can provide transportation by cars as far as Rough and Ready, and also wagons; but that their removal may be made with as little discomfort as possible it will be necessary for you to help the families from Rough and Ready to the cars at Lovejoy’s. If you consent I will undertake to remove all families in Atlanta who prefer to go South to Rough and Ready, with all their movable effects, viz, clothing, trunks, reasonable furniture, bedding, &c., with their servants, white and black, with the proviso that no force shall be used toward the blacks one way or the other. If they want to go with their masters or mistresses they may do so, otherwise they will be sent away, unless they be men, when they may be employed by our quartermaster. Atlanta is no place for families or non-combatants and I have no desire to send them North if you will assist in conveying them South. If this proposition meets your views I will consent to a truce in the neighborhood of Rough and Ready, stipulating that any wagons, horses, or animals, or persons sent there for the purposes herein stated shall in no manner be harmed or molested, you in your turn agreeing that any cars, wagons, carriages, persons, or animals sent to the same point shall not be interfered with. Each of us might send a guard of, say, 100 men to maintain order, and limit the truce to, say, two days after a certain time appointed. I have authorized the mayor to choose two citizens to convey to you this letter and such documents as the mayor may forward in explanation, and shall await your reply.

I have the honor to be, your obedient servant,

W. T. SHERMAN,

Major-General, Commanding.

——————————

Maj. Gen. W. T. SHERMAN.

Commanding U.S. Forces in Georgia:

GENERAL: Your letter of yesterday’s date [7th] borne by James M. Ball and James R. Crew, citizens of Atlanta, is received. You say therein “I deem it to be to the interest of the United States that the citizens now residing in Atlanta should remove,” &c. I do not consider that I have any alternative in this matter. I therefore accept your proposition to declare a truce of two days, or such time as may be necessary to accomplish the purpose mentioned, and shall render all assistance in my power to expedite the transportation of citizens in this direction. I suggest that a staff officer be appointed by you to superintend the removal from the city to Rough and Ready, while I appoint a like officer to control their removal farther south; that a guard of 100 men be sent by either party, as you propose, to maintain order at that place, and that the removal begin on Monday next. And now, sir, permit me to say that the unprecedented measure you propose transcends, in studied and ingenious cruelty, all acts ever before brought to my attention in the dark history of war. In the name of God and humanity I protest, believing that you will find that you are expelling from their homes and firesides the wives and children of a brave people.

I am, general, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

J. B. HOOD,

General.

————————————

General J. B. HOOD, C. S. Army, Comdg. Army of Tennessee:

GENERAL: I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt of your letter of this date [9th], at the hands of Messrs. Ball and Crew, consenting to the arrangements I had proposed to facilitate the removal south of the people of Atlanta who prefer to go in that direction. I inclose you a copy of my orders, which will, I am satisfied, accomplish my purpose perfectly. You style the measure proposed “unprecedented,” and appeal to the dark history of war for a parallel as an act of “studied and ingenious cruelty.” It is not unprecedented, for General Johnston himself, very wisely and properly, removed the families all the way from Dalton down, and I see no reason why Atlanta should be excepted. Nor is it necessary to appeal to the dark history of war when recent and modern examples are so handy. You, yourself, burned dwelling-houses along your parapet, and I have seen to-day fifty houses that you have rendered uninhabitable because they stood in the way of your forts and men. You defended Atlanta on a line so close to town that every cannon shot and many musket shots from our line of investment that overshot their mark went into the habitations of women and children. General Hardee did the same at Jonesborough, and General Johnston did the same last summer at Jackson, Miss. I have not accused you of heartless cruelty, but merely instance these cases of very recent occurrence, and could go on and enumerate hundreds of others and challenge any fair man to judge which of us has the heart of pity for the families of a “brave people.” I say that it is kindness to these families of Atlanta to remove them now at once from scenes that women and children should not be exposed to, and the “brave people” should scorn to commit their wives and children to the rude barbarians who thus, as you say, violate the laws of war, as illustrated in the pages of its dark history. In the name of common sense I ask you not to appeal to a just God in such a sacrilegious manner; you who, in the midst of peace and prosperity, have plunged a nation into war, dark and cruel war; who dared and badgered us to battle, insulted our flag, seized our arsenals and forts that were left in the honorable custody of peaceful ordnance sergeants; seized and made “prisoners of war” the very garrisons sent to protect your people against negroes and Indians long before any overt act was committed by the, to you, hated Lincoln Government; tried to force Kentucky and Missouri into rebellion, spite of themselves; falsified the vote of Louisiana, turned loose your privateers to plunder unarmed ships; expelled Union families by the thousands; burned their houses and declared by an act of your Congress the confiscation of all debts due Northern men for goods had and received. Talk thus to the marines, but not to me, who have seen these things, and who will this day make as much sacrifice for the peace and honor of the South as the best born Southerner among you. If we must be enemies, let us be men and fight it out, as we propose to do, and not deal in such hypocritical appeals to God and humanity. God will judge us in due time, and He will pronounce whether it be more humane to fight with a town full of women, and the families of “a brave people” at our back, or to remove them in time to places of safety among their own friends and people.

W. T. SHERMAN,

Major-general, Commanding.

———————————-

Maj. Gen. W. T. SHERMAN:

SIR: We, the undersigned, mayor and two of the council for the city of Atlanta, for the time being the only legal organ of the people of the said city to express their wants and wishes, ask leave most earnestly, but respectfully, to petition you to reconsider the order requiring them to leave Atlanta. At first view it struck us that the measure would involve extraordinary hardship and loss, but since we have seen the practical execution of it so far as it has progressed, and the individual condition of the people, and heard their statements as to the inconveniences, loss, and suffering attending it, we are satisfied that the amount of it will involve in the aggregate consequences appalling and heart-rending. Many poor women are in advanced state of pregnancy; others now having young children, and whose husbands, for the greater part, are either in the army, prisoners, or dead. Some say, “I have such an one sick at my house; who will wait on them when I am gone?” Others say, “what are we to do? We have no house to go to, and no means to buy, build, or rent any; no parents, relatives, or friends to go to.” Another says, “I will try and take this or that article of property, but such and such things I must leave behind, though I need them much.” We reply to them, “General Sherman will carry your property to Rough and Ready, and General Hood will take it thence on,” and they will reply to that, “but I want to leave the railroad at such place and cannot get conveyance from there on.”

We only refer to a few facts to try to illustrate in part how this measure will operate in practice. As you advanced the people north of this fell back, and before your arrival here a large portion of the people had retired south, so that the country south of this is already crowded and without houses enough to accommodate the people, and we are informed that many are now staying in churches and other outbuildings. This being so, how is it possible for the people still here (mostly women and children) to find any shelter? And how can they live through the winter in the woods? No shelter or subsistence, in the midst of strangers who know them not, and without the power to assist them much, if they were willing to do so. This is but a feeble picture of the consequences of this measure. You know the woe, the horrors and the suffering cannot be described by words; imagination can only conceive of it, and we ask you to take these things into consideration. We know your mind and time are constantly occupied with the duties of your command, which almost deters us from asking your attention to this matter, but thought it might be that you had not considered this subject in all of its awful consequences, and that on more reflection you, we hope, would not make this people an exception to all mankind, for we know of no such instance ever having occurred; surely none such in the United States, and what has this helpless people done, that they should be driven from their homes to wander strangers and outcasts and exiles, and to subsist on charity? We do not know as yet the number of people still here; of those who are here, we are satisfied a respectable number, if allowed to remain at home, could subsist for several months without assistance, and a respectable number for a much longer time, and who might not need assistance at any time. In conclusion, we most earnestly and solemnly petition you to reconsider this order, or modify it, and suffer this unfortunate people to remain at home and enjoy what little means they have.

Respectfully submitted.

JAMES M. CALHOUN,

Mayor.

E. E. RAWSON,

S.C. WELLS,

Councilmen.

——————————–

JAMES M. CALHOUN, Mayor, E. E. RAWSON, and S. C. WELLS,

Representing City Council of Atlanta:

GENTLEMEN: I have your letter of the 11th, in the nature of a petition to revoke my orders removing all the inhabitants from Atlanta. I have read it carefully, and give full credit to your statements of the distress that will be occasioned by it, and yet shall not revoke my orders, simply because my orders are not designed to meet the humanities of the case, but to prepare for the future struggles in which millions of good people outside of Atlanta have a deep interest. We must have peace, not only at Atlanta but in all America. To secure this we must stop the war that now desolates our once happy and favored country. To stop war we must defeat the rebel armies that are arrayed against the laws and Constitution, which all must respect and obey. To defeat these armies we must prepare the way to reach them in their recesses provided with the arms and instruments which enable us to accomplish our purpose. Now, I know the vindictive nature of our enemy, and that we may have many years of military operations from this quarter, and therefore deem it wise and prudent to prepare in time. The use of Atlanta for warlike purposes is inconsistent with its character as a home for families. There will be no manufactures, commerce, or agriculture here for the maintenance of families, and sooner or later want will compel the inhabitants to go. Why not go now, when all the arrangements are completed for the transfer, instead of waiting till the plunging shot of contending armies will renew the scenes of the past month? Of course, I do not apprehend any such thing at this moment, but you do not suppose this army will be here until the war is over. I cannot discuss this subject with you fairly, because I cannot impart to you what I propose to do, but I assert that my military plans make it necessary for the inhabitants to go away, and I can only renew my offer of services to make their exodus in any direction as easy and comfortable as possible. You cannot qualify war in harsher terms than I will. War is cruelty and you cannot refine it, and those who brought war into our country deserve all the curses and maledictions a people can pour out. I know I had no hand in making this war, and I know I will make more sacrifices to-day than any of you to secure peace. But you cannot have peace and a division of our country. If the United States submits to a division now it will not stop, but will go on until we reap the fate of Mexico, which is eternal war. The United States does and must assert its authority wherever it once had power. If it relaxes one bit to pressure it is gone, and I know that such is the national feeling. This feeling assumes various shapes, but always comes <ar78_419> back to that of Union. Once admit the Union, once more acknowledge the authority of the National Government, and instead of devoting your houses and streets and roads to the dread uses of war, and this army become at once your protectors and supporters, shielding you from danger, let it come from what quarter it may. I know that a few individuals cannot resist a torrent of error and passion such as swept the South into rebellion, but you can part out so that we may know those who desire a government and those who insist on war and its desolation. You might as well appeal against the thunder-storm as against these terrible hardships of war. They are inevitable, and the only way the people of Atlanta can hope once more to live in peace and quiet at home is to stop the war, which can alone be done by admitting that it began in error and is perpetuated in pride.

We don’t want your negroes or your horses or your houses or your lands or anything you have, but we do want, and will have, a just obedience to the laws of the United States. That we will have, and if it involves the destruction of your improvements we cannot help it. You have heretofore read public sentiment in your newspapers that live by falsehood and excitement, and the quicker you seek for truth in other quarters the better for you. I repeat then that by the original compact of government the United States had certain rights in Georgia, which have never been relinquished and never will be; that the South began war by seizing forts, arsenals, mints, custom-houses, &c., long before Mr. Lincoln was installed and before the South had one jot or title of provocation. I myself have seen in Missouri, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Mississippi hundreds and thousands of women and children fleeing from your armies and desperadoes, hungry and with bleeding feet. In Memphis, Vicksburg, and Mississippi we fed thousands upon thousands of the families of rebel soldiers left on our hands and whom we could not see starve. Now that war comes home to you, you feel very different. You deprecate its horrors, but did not feel them when you sent car-loads of soldiers and ammunition and molded shells and shot to carry war into Kentucky and Tennessee, and desolate the homes of hundreds and thousands of good people who only asked to live in peace at their old homes and under the Government of their inheritance. But these comparisons are idle. I want peace, and believe it can now only be reached through union and war, and I will ever conduct war with a view to perfect an early success. But, my dear sirs, when that peace does come, you may call on me for anything. Then will I share with you the last cracker, and watch with you to shield your homes and families against danger from every quarter. Now you must go, and take with you the old and feeble, feed and nurse them and build for them in more quiet places proper habitations to shield them against the weather until the mad passions of men cool down and allow the Union and peace once more to settle over your old homes at Atlanta.

Yours, in haste,

W. T. SHERMAN,

Major-General, Commanding.

———————————-

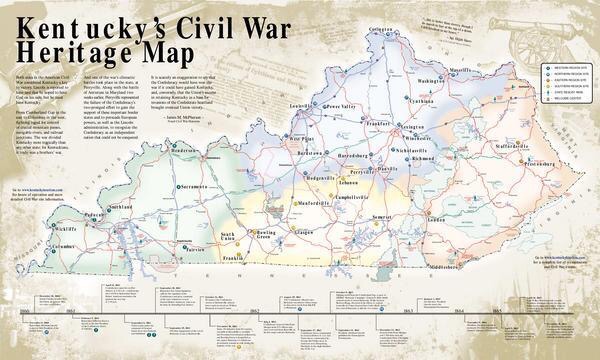

Kentucky…Better Left Alone. Polk’s Blunder

Today in History, September 3: 1861 – Unintended consequences. At the outset of the Civil War, Kentucky declared itself neutral, primarily because the state had an almost equal allegiance to both sides. President Lincoln, on precarious footing with the border states, was careful to respect the neutrality. Kentucky covered key geography and the North couldn’t afford to push it to the South.

Confederate General Leonidus Polk (2nd cousin to President Polk), was not quite as politically astute, making one of the worst blunders of the war. He made the decision to secure the strategic town of Columbus, Kentucky. The act pushed the fence sitting Kentucky government to the other side, and they asked for Federal protection from the Confederate “invaders”. This came in the form of Gen. US Grant’s Army forcing Polk out.

While there were Kentucky units that fought for both the Union and the Confederacy, the state itself was now officially Union.

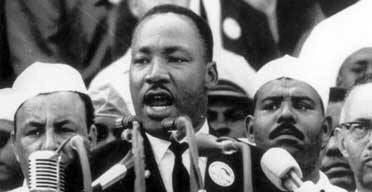

“I Have a Dream”

Today in History, August 28: 1963 – “I still have a dream, a dream deeply rooted in the American dream – one day this nation will rise up and live up to its creed, ‘We hold these truths to be self evident: that all men are created equal.’ I have a dream . . .” Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr speaks before a crowd of 250,000 civil rights advocates (of several races), standing on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial, paying his respects to the man who signed the Emancipation Proclamation and calling for an end to racial division in America. He was the 16th of 18 speakers, but this became his day in history. The event was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, organized as a mass public demonstration in support of Civil Rights Legislation proposed by President John F. Kennedy earlier that year. Dr. King’s speech became a landmark in our history as he tied everything from the Constitution to the Emancipation Proclamation together to point out the injustice still prevalent at that time, and to share his vision of a time when the color of one’s skin would be unimportant.

Here is the text of his speech:

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of their captivity.

But one hundred years later, the Negro still is not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languished in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. And so we’ve come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

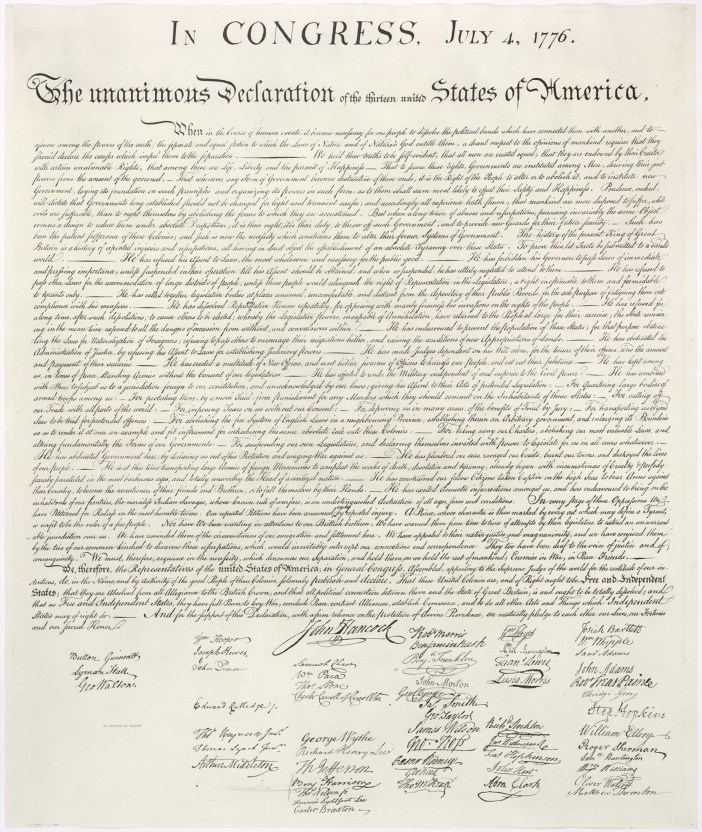

In a sense we’ve come to our nation’s capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men, yes, black men as well as white men, would be guaranteed the “unalienable Rights” of “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked “insufficient funds.”

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And so, we’ve come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

“I Have a Dream”

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of Now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God’s children.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro’s legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. And those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. And there will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people, who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice: In the process of gaining our rightful place, we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force.

The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to a distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom.

We cannot walk alone.

And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall always march ahead.

We cannot turn back.

There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, “When will you be satisfied?” We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the negro’s basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their self-hood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating: “For Whites Only.” We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until “justice rolls down like waters, and righteousness like a mighty stream.”¹

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. And some of you have come from areas where your quest — quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.

Let us not wallow in the valley of despair, I say to you today, my friends.

And so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.”

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at the table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day, down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of “interposition” and “nullification” — one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers.

I have a dream today!

I have a dream that one day every valley shall be exalted, and every hill and mountain shall be made low, the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight; “and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed and all flesh shall see it together.”

This is our hope, and this is the faith that I go back to the South with.

With this faith, we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith, we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith, we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day.

And this will be the day — this will be the day when all of God’s children will be able to sing with new meaning:

My country ’tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing.

Land where my fathers died, land of the Pilgrim’s pride,

From every mountainside, let freedom ring!

And if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.

And so let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire.

Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York.

Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania.

Let freedom ring from the snow-capped Rockies of Colorado.

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California.

But not only that:

Let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia.

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee.

Let freedom ring from every hill and molehill of Mississippi.

From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, and when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual:

Free at last! Free at last!

Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!

Today in History, August 12: 1867 – “Hon. EDWIN M. STANTON, Secretary of War.

Sir: By virtue of the power and authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and laws of the United States, you are hereby suspended from office as Secretary of War, and will cease to exercise any and all functions pertaining to the same.

You will at once transfer to General Ulysses S. Grant, who has this day been authorized and empowered to act as Secretary of War ad interim, all records, books, and other property now in your custody and charge.

ANDREW JOHNSON”

Volatile politics is nothing new in America. For his second term, President Lincoln had chosen Democrat Andrew Johnson as his vice President because he was from a border state, loyal to the Union, but a Southerner.

When Johnson assumed office after Lincoln’s assassination, he did not enforce reconstruction in the South as strongly as Lincoln’s contemporaries in the cabinet and the Congress wanted. The battle was ongoing, with Congress passing the Tenure of Office Act to prevent Johnson from firing cabinet members that did not agree with him.

Most prominent was Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. On this date Johnson suspended Stanton and replaced him with the popular Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, who resigned the position once Congress reconvened and voted not to remove Stanton. Stanton refused to leave, to the point that in February of 1868 when Johnson formally fired him, Stanton barricaded himself in his office in the War Department.

The “radical” Republicans in the House voted to impeach Johnson over the ordeal, but the Senate, after a lengthy trial, kept him in office.

Life, Liberty and the Pursuit of Happiness. A Date Full of Historic Significance!

Today in History, July 4: This is my favorite day of the year to post, not only because it is America’s birthday, but because the date is so rich in American History.

1754 – During the French and Indian Wars, a young colonial member of the British Army abandons “Fort Necessity” after surrendering it to the French the day before. The officer, 22-year-old Lt. George Washington had also commanded British forces in the first battle of the war on the American continent weeks before. The French and Indian Wars were only part of a global conflict between England and France, the Seven Years War. His experience here would serve Washington well in our War for Independence.

1776 – The second Continental Congress adopts the Declaration of Independence from England after years of conflict as colonists, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

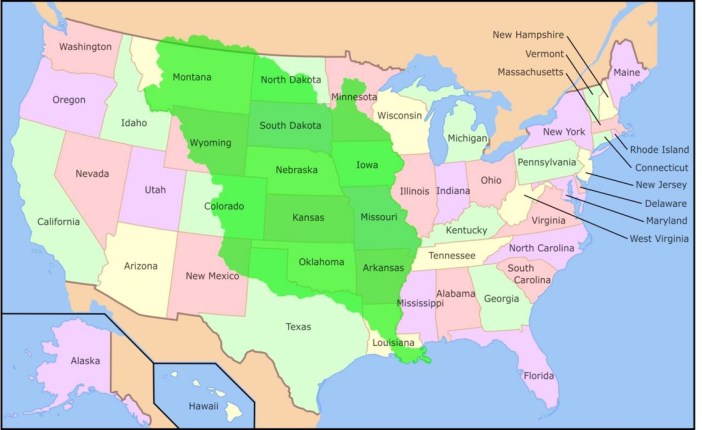

1803 – President Thomas Jefferson announces the signing of a treaty in Paris formalizing the Louisiana Purchase, effectively doubling the size of the United States in one day for $15M.

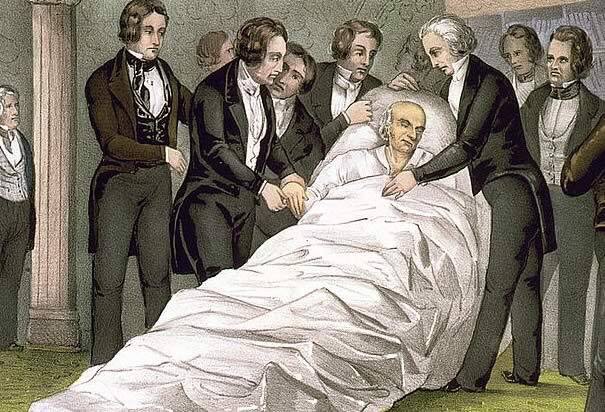

1826 – 50 years after the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, two of it’s signers, second President John Adams and third President Thomas Jefferson, die on the same day. The two had become bitter political enemies for years (Adams a devout Federalist, Jefferson an equally devout state’s rights man, in addition to vicious political vitriol the two had exchanged). But in 1812 they made amends and began a years’ long correspondence, making them good friends again. It is said that Adams’ last words were, “Jefferson survives”. He was wrong, Jefferson had died five hours before. Many Americans at the time saw their death on the same day 50 years after the Nation’s birth as a divine sign.

1863 – Confederate General John C. Pemberton surrenders Vicksburg, Mississippi to Union General Ulysses S. Grant. Pemberton had sent a note asking for terms on the 3rd, and initially Grant gave his usual “unconditional surrender” response. He then thought about what he would do with 30,000 starving Southern troops, who he had lay siege to since May 18th, and granted them parole, accepting the surrender on the 4th. The capture of Vicksburg effectively secured the main artery of commerce for the Union and cut off of the Confederate states west of the Mississippi (and their supplies) from the South. Grant’s parole of the rebels would come back to haunt him, as the Confederacy did not recognize it’s terms and many of the parolees fought again…which came back to haunt the Confederacy because as a result the Union stopped trading prisoners. Celebrated as a great victory by the North, but by Vicksburg not so much. The Citizens of the Southern city had to take to living in caves during the siege as US Navy and Army continuously bombarded their homes. Starving and desperate, they saw Grant’s waiting a day to accept surrender as malicious. Independence Day would not be officially celebrated in Vicksburg for a generation.

1863 – On the same day, half a continent away, Confederate General Robert E. Lee led his defeated Army of Northern Virginia south away from the Battle of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. This was no small matter…”Bobby Lee” had been out-foxing and out-maneuvering multiple Union Generals practically since the war began. No official surrender here…Lee’s army would survive to fight another day. While both battles were turning points, they did not spell the end of the South as many believe. There were years of hard, bitter fighting still to come with ghastly losses in life and injury. Gettysburg was, however, the last serious attempt by the South to invade the North.

1913 – President Woodrow Wilson addresses the Great 50 Year Reunion of Gettysburg, attended by thousands of Veterans from both sides, who swapped stories, dined together…and it would seem, forgave for a time.

1939 – “I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of the Earth”. After 17 years as a beloved member of Major League Baseball, New York Yankee Lou Gehrig stands in Yankee Stadium and says goodbye to his fans, having been diagnosed with a terminal disease that now bears his name. I doubt there was a dry eye in the house. I’ve posted the video below.

God Bless America! And thank you to our service men and women that continue to make our freedoms possible.

Literature Starts a Fire

Today in History, June 5: 1851 – “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, or “Life Among the Lonely”, by Harriett Beecher Stowe is first published in an abolitionist weekly magazine. The story brought the life of a slave to the masses when a publisher picked it up and printed it in book form, making it an international sensation. The book set afire the slavery / anti-slavery camps in the nation. In 1862, when President Lincoln played host to Ms. Stowe in the White House, he is reported to have greeted her with, “So this is the little lady who made this big war?”. In book form, Uncle Tom’s Cabin would be the number one bestseller of the 19th century, except of course for the Bible.